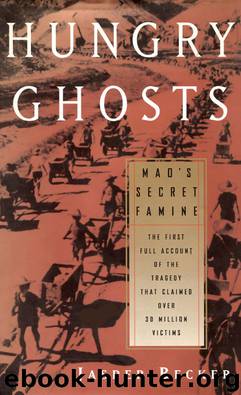

Hungry Ghosts by Jasper Becker

Author:Jasper Becker

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: eBookPartnership.com

Published: 2013-08-28T04:00:00+00:00

12

In the Prison Camps

‘The Buddhist classics speak of six ways one can be reincarnated. There is hell, hungry ghosts, animals, Asura, humans and heaven, and the worst of these is to become a hungry ghost.’ Zhang Xianliang, Grass Soup

Millions were sucked into China’s vast network of prisons and labour colonies during the Great Leap Forward, indeed more than in any other period after 1949. And, with the onset of the famine, these institutions became in effect death camps.1 In his book Laogai: The Chinese Gulag, Harry Wu, who himself spent nineteen years in the camps, estimates that during this period the number of political prisoners peaked at close to 10 million. (By comparison, in the forty years up to 1989, he estimates that a total of 30—40 million were arrested and convicted for political reasons.2)

During the Three Red Banners movement that began in 1958, anyone who expressed dissatisfaction with the hardships caused by Mao Zedong and the Communist Party leader’s impractical policies, or anyone who showed resentment over the following three years of hunger and food shortages, was seen as directly threatening the stability of the Communist Party’s dictatorship. The Communist Party responded with draconian measures of suppression.

The majority, around 70 per cent, of those imprisoned were sentenced to ‘reform through labour’ and held in the labour reform camps of the Ministry of Public Security. Such prisons contain both common and political criminals. As in the Soviet Gulag, intellectuals and political prisoners were treated more harshly in these labour camps than real criminals, who were considered easier to reform and indoctrinate. Harry Wu claims that political prisoners were given longer sentences, reprimanded and beaten more often and given lower food rations. They also found it harder to adapt to the treacherous dog-eat-dog environment in the camps and were not able to cope with the physical demands made on them which, in turn, led to punishments for failing to meet their work quotas and still lower rations.

In exceptional cases, life could be better for intellectuals. One interviewee from Guangzhou said both her parents were sent to labour camps during the famine. Her father never returned, dying in a camp in 1975, but her mother was sent to the Yingde labour farm in Guangdong province which grows tea. As a professional player of the erhu, a Chinese musical instrument, she was invited to join a prison orchestra which toured other camps. She was given four meals a day and ate better than did her children left behind in Guangzhou. Gao Ertai, a painter, only survived the camps because he was summoned by the Gansu Party Secretary, Zhang Zhongliang, to paint a tableau celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Daqing oilfield. At that stage, his legs were so swollen by oedema that he had to be lifted up on to the scaffolding to complete the huge tableau.3

However, most of those arrested were not intellectuals but rather, as Harry Wu points out, ‘peasants driven to drastic acts or rebellion by hunger and dissatisfaction with living conditions’.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4390)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4211)

World without end by Ken Follett(3476)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3467)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3203)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3174)

The Queen of Nothing by Holly Black(2599)

City of Djinns: a year in Delhi by William Dalrymple(2555)

Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Treasures of Central Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2464)

India's Ancient Past by R.S. Sharma(2454)

Inglorious Empire by Shashi Tharoor(2437)

Tokyo by Rob Goss(2429)

In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl's Journey to Freedom by Yeonmi Park(2392)

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(2373)

India's biggest cover-up by Dhar Anuj(2354)

The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia by Peter Hopkirk(2349)

Goodbye Madame Butterfly(2253)

Batik by Rudolf Smend(2181)

Living Silence in Burma by Christina Fink(2071)